In this paper, Giacomin studies the roots, evolution, contemporary state, and future direction of Human Centred Design practices.

Interestingly, the roots of the discipline can be traced to fields of ergonomics, computer science, and artificial intelligence. International standards such as ‘ISO 9241-210 Ergonomics of human-centred systems interaction’ allude to a technical engineering approach that applies understandings of human factors (i.e. ergonomics) to create more usable interactive systems.

These technological/engineering approaches to human-centred design have since evolved to embody the processes they promote. Early approaches maintained a ‘goal-directed’ and ‘preconceived schema’ focus, limiting the process to predetermined areas of focus and by extension, limiting the possibility of broader exploration, learning, and interactivity (similar to traditional design practices where designer’s personal creative process directs the focus of questions, insights and activities to derive material and technological directions for a design). Basically, designs were altered in response to user feedback without more broadly questions if this is what the design was actually something the user needed or if it actually helped them full-fill their goals.

Thinking in the discipline evolved to understand the processes of communicating and learning (which cannot be fully anticipated by initial objectives, perceptions, and physical designs) as being fundamental to deriving views (on needs, desires, and experiences), interactions, and meanings to design ‘products, systems, and services which are physically, perceptually, cognitively, and emotionally intuitive” to their identified users. By adopting “techniques which communicate, interact, empathise and stimulate users” we can often gain insights that “transcend that which the users themselves actually realise”.

“What began as a psychological study of human beings on a scientific basis for the purposes of machine design has evolved to become the measurement and modelling of how people interact with the world, what they perceive and experience, and what meaning they create”

In this frame, the scope of human centred design seems to extend beyond that of traditional design disciplines to not only include determining the project brief but also understanding broader psychological, economic, and sociological factors that unavoidably shape how a designed product or service is experienced. In this sense human centred design is concerned more broadly with social acceptance, commercial success, brand identity, and business strategy.

Giacomin includes this observation in his paper, noting that “in recent years many businesses have shifted their emphasis away from matters of technology and manufacture, moving instead towards a growing preoccupation with how their products, systems or services are perceived and experienced by the customer” and that 70-80% of new products that fail do so because of a failure to understand user needs. “Empirical evidence from product failures supports the claim that human centred design improves commercial success”. As a result, the paradigm is being applied in various areas of commercial activity, from marketing, through to corporate identity, and even business strategy. Its clear that “addressing the perceptual, cognitive and emotional needs of customers” is a sensible business practice; as is the emerging practice of co-developing and co-evolving the business branding to derive organisational values and discourse from a full range of stakeholders”.

Finally, human centred design business strategies present a means through which to “develop products, systems, and services based on matters of perception, interaction, learning, and meaning”. Traditional strategies of ‘Technology-Push’ (Research & Development + Manufacturing + Marketing = Sales) and ‘Market-Pull’ (Marketing + Research & Development + Manufacturing = Sales) are not completely compatible with a HCD approach. Technology pull approaches are usually based on technical novelty and optimisation; while Market-Pull involves significant customer interaction, it does so within the limits and confines of existing products, systems, services and meanings, producing only incremental innovation through the process. Giacomin instead propose a new HCD business strategy, Hybrid Market-Pull which involves businesses proposing new meaning s and possible futures to people, then responding to commentary and feedback.

Human Centred Design (HCD) Toolbox

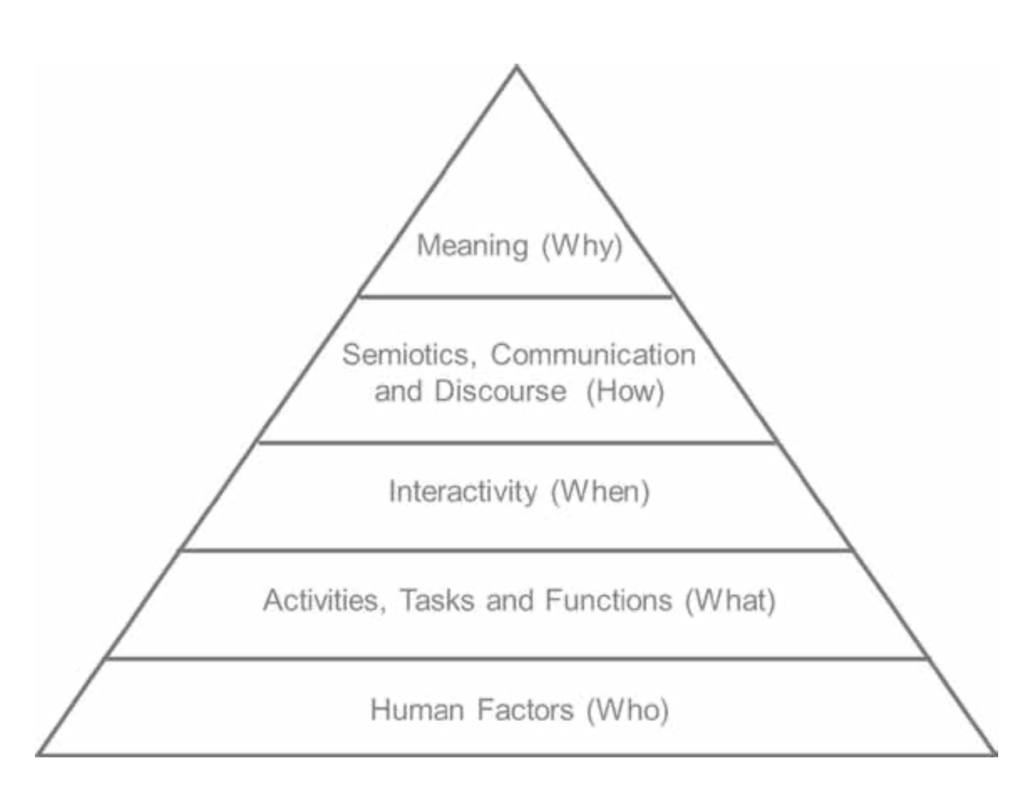

The methodology behind human centred design practices can be thought of as a process of asking an incremental set of questions about “the relationship a design artefact either creates for a person or facilitates” that “span [from] the spectrum from the physical nature of people’s interaction” through to the metaphysical. These include Why (Meaning), How (Semiotics, Communication, and discourse), When (Interactivity), What (Activities, Tasks, and Functions), and Who (Human Factors).

“Designs whose characteristics answer questions and curiosities which are further up the pyramid would be expected to offer a wider range of affordances to people, and to embed themselves deeper within people’s minds and everyday lives. In particular, a product, system or service which can introduce a new meaning into a person’s life would be expected to offer ample opportunities for commercial success and for brand development, as historic examples such as Ferrari sports cars or Apple IPods seem to suggest.”

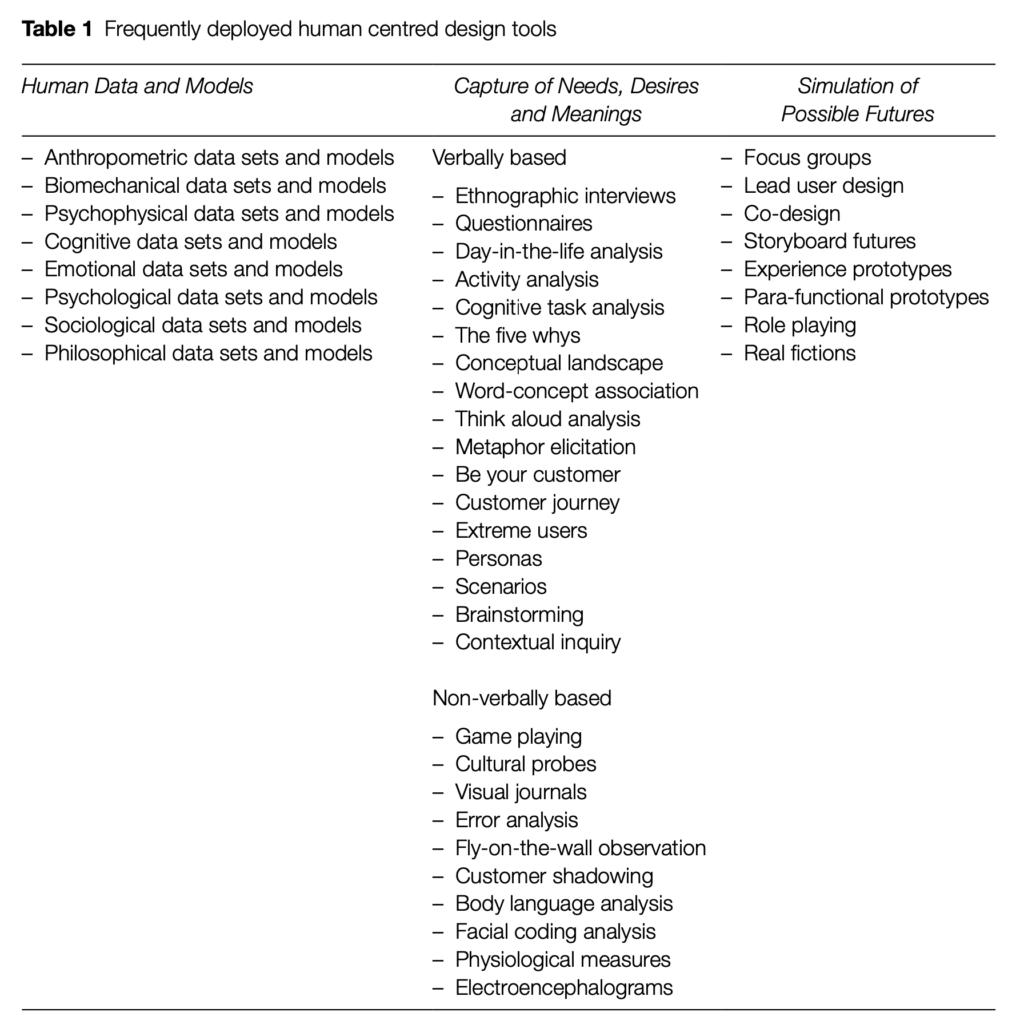

Tools for facilitating this process can be classified according to their intended use: Statistically derived data-sets about people (such as anthropometric, biomechanical, cognitive, emotional, psychophysical, psychological, and sociological data and models) inform the process and the boundaries within which to operate, Methodologies and techniques offer a way to guide interaction in a way the facilitates the detection of meanings, desires, and needs, and finally Co-design and Speculative techniques that simulate intuitions, opportunities, and possible futures.

The below table offers a summary of the various tools arranged temporary from left to right: from historical data, to current contexts and values, to siumulating future possibilities.